Soon after I took the last photo, he admonished me. At first I did not understand what was happening. I nodded and smiled not entirely sure if I should. The admonition felt heavy and full of dread. He seemed disappointed over my actions. For a moment I felt like he knew something about me, who I was, and what I was doing in Venice, more specifically what I was doing in the Venice Jewish Ghetto.

The words I gathered were these:

Look with your eyes to connect with your soul and mind. When you look with your phone, the images go to the phone. You missed an opportunity to connect with the work and let the work talk to you. Look with your eyes.

I tried to explain that I just met the artist whose work he was selling in his gallery. I wanted to tell him that the artist, Michal Meron and I had a nice conversation, that I bought some of her pieces, that she was the one who told me to come to his gallery to see another one of her pieces. But when I tried, he insisted and reprimanded me once again. Nodding and smiling as unsure I was, it seemed to be the only viable option. I said, grazie and left.

Reflecting on what just happened as I was walking, I realized that yes, I had received a reprimand from someone who seemed to be a rabbi. His words as challenging as they were to understand, stayed with me. This encounter happened on Friday and I still think about it…

There are not many things that enrapture me more than looking at artwork. I love to look and to observe almost obsessively when I am visiting a museum or a gallery. I wander in the space while my thoughts entangle me with imaginary stories about what the surroundings might have been or might be around the artwork.

The majority of the work we saw in our study abroad trip was religious in nature. Except for our visit to the MAXXI and the Williem de Kooning exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Academia di Venezia, we were surrounded by intensely religious work. The artworks told stories. There was always a narrative; be it about the creation, the annunciation, the birth of Jesus, his death, his resurrection, the lives of the disciples, as well as other religious stories.

The narratives in the artworks include a number of details easily missed unless one is really looking. When one pays close attention and the works are looked at chronologically, one notices changes. For instance, the depiction of Jesus as a blond and clear skin man was something that happened over time. The halos also became lighter and brighter over the course of time as well. And breasts as a source of nourishment gradually changed to become something to behold, to look at, and to admire.

Still, in spite of these observations the words of the rabbi are still in my mind. Am I that trivial? Do I not connect enough with the artwork I am observing? Yes, I take pictures because I want to document what I am seeing, I want to share with others, and I want to use it as a source of inspiration. Most of us take pictures of the things that mean something to us. We want to memorialize a moment. But, are we missing something? Do we not remember enough? How long should we look at artworks? How short is too short? In what way do we need to look at artworks in order to connect with them? Moreover, should our connections live only in our memories? But, then, how do we build collective memories?

The words of the rabbi perhaps point to something more profound; a shift in how we approach the world. In general, it would seem that we reduce our appreciation of the world to a click of the phone be it for a selfie or for the grid on Instagram. We want to curate our experiences to then share them with the world. Are we that superficial?

I keep asking myself these questions. Sometimes I think that the rabbi judged me harshly. After all, he decided who I was, he decided about my intentions, and he had no idea that I feed my eyes, my mind, and my soul in order to create.

The studio and shop of Michal Meron was an experience in and of itself. Her work captured my attention because of its playfulness and use of color. She had series of works on the books of the OId Testament, specifically the Psalms. They were beautiful. I was fascinated by the stories she shared about the segregation of the Jewish people to Venice. I was fascinated with the calligraphic script and her letters.

She asked me what I did for a living. I explained that I was a designer and design educator who practiced calligraphy and lettering. She and her assistant directed me to the gallery across to see a particular piece made by her using the micrography technique where the letters created the shape of the persons. It is similar to calligrams. We went to the gallery where the piece was by the window.

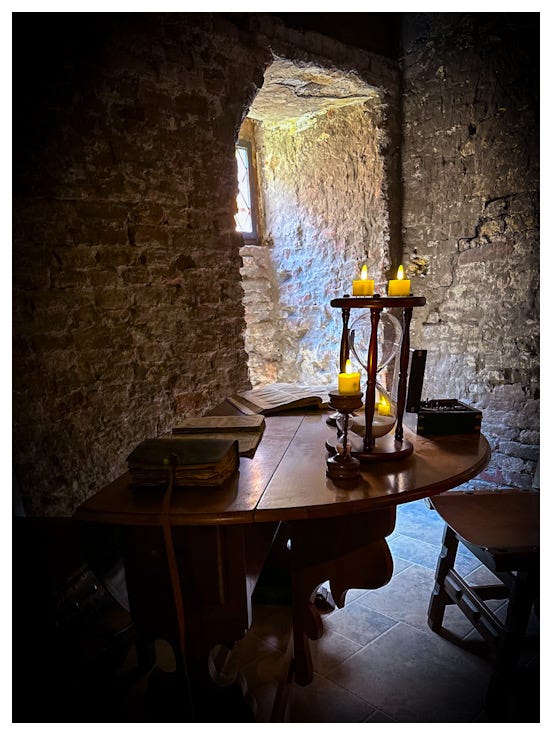

And I met the rabbi. He was in charge of the gallery. I looked at the piece above in the photos. There was so much to look at not only because the micrography technique was very different to Ms. Meron’s usual work but also because I was fascinated with the attention to detail and the monochromatic nature of the piece. The photos above do not do it justice. There was too much glare from the lights. The work in the gallery was very similar to the work in Ms. Meron’s studio and shop. I took some photos and as I was walking away, the rabbi’s words came as a warning.

I left with sadness.

Love,

Alma