Fancy brains…

An essay…

Years ago a friend referred to me as fancy brains because of my work as a creative. The moniker stuck with me so much that I named several of my devices fancy brains, fancy soul, and so on. If you think about it though, our brains are fancy. There is so much going on inside of it while we are blissfully unaware of it all. As it should be. It is not a habit of anyone I know to sit down and proceed to list all the things their brain is doing—unless of course, you are a detective. Say, we enter a room and we start: brain, notice the wall, its color, texture, angles, corners, openings, holes, pictures or not, height, width, joints, sideboards, doors openings, also notice the floor, its color, texture, connection to the wall, how wide is it, the chairs, the tables, what everyone is wearing, and so on. Or we go to a place with a lot of visual stimulation, say an adventure park, and we start consciously listing every single item we come in contact with or pass by. Yet, conscious or not, that is exactly what the brain is doing: registering. Sometimes I feel we can say “I am only aware of what I want to be aware of…” Because we can’t focus on or process it all.

We fail to live between habit and novelty. We need patterns and routine to work efficiently on some things but we also need novelty to wake up our senses. A physical exercise routine needs to be varied frequently or else the body becomes so efficient that it bypasses the friction and effort it takes to develop x skill. The adequate amount of friction allows the body to build or strengthen something. In fact, personal trainers keep you busy changing the routine so that the body is constantly working to burn those calories or build x muscle or muscles.

I came across a perhaps “too simple to be true” principle recently. The book Your Brian on Art written by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross discusses the positive if not, essential impact of a regular art practice and/or exposure for our brains. Whether it is in its development as when we are children, or maintenance, or healing after an injury, the authors explain at length the massive amount of support the arts provide to the brain. It is kind of saying, the brain needs to be fancy. —Yeah, I know. I had to insert that there.

The simple principle is this: 20 minutes of art exposure a day are as essential for the brain’s good health as 30 minutes of daily moderate exercise is to the body. In an interview by Nicholas Wilton on his podcast and website Art2Life, the authors discuss the notion that even 20 minutes a day provides the brain with much needed stimulation to function optimally. Does it sound simple? Yep. Does it sound easy? Yep. Does it sound even appealing? Yep. Yet, I know people whose lives are so tied up and busy that the thought of spending 20 minutes doing something they can’t measure, or feel immediately is completely alien to them and utterly unappealing.

We like to follow a script. If I do x, y will happen, and then z which is the ultimate goal. And we like to follow that script. Any deviation from it, is threatening. I have advised a good number of students for whom this is and has been a huge problem. The sense of failure or inadequacy they feel when even the smallest thing does not go according to plan is devastating. While such focus is needed, it is also paralyzing. We like things to be tangible, concrete, and achievable. Thus, spending 20 minutes doing who knows what that may or may not look great is definitely unappealing to many.

There is much we do not engage in, not only because its benefits are not concrete and immediate but also because we believe that a complete sense of mastery must be attained beforehand. If I had a penny for every time I hear things like “I am not good at ____.” Well, I’d be rich.

True, a realistic sense of our abilities and skills is healthy, but not all of us need to be masters to do something. When I started dancing back in the mid nineties, I was an adult. I had danced in my teenage years informally. I never had formal training. My friends and I would watch things we wanted to learn and we would practice. Later on, when I came back to it, I started from the bottom since it had been over a decade of my dancing times. In one modern dance class I asked the professor if anyone was ever late in life to dance and dance well. Her answer was wise and comforting. She said that while being realistic that at this stage in your life you will not be a prima ballerina, it is also realistic to consider that you can attain mastery. It is all contingent on what you are dancing for. That was liberating for me.

The same is true for the arts. Some of us have abilities in one area and others in other areas. And there is the time factor. Not all of us will have the time to become a master in whatever we want to practice, nor should we. There are things we are invited to enjoy as spectators. There are other things we are definitely invited to be the creators. For some of us the arts, in whichever form, is an invitation. And guess what? That counts for your 20 minutes of art. Visiting a gallery, a museum, listening to music, singing in the shower, dancing when cleaning, and letting your brain enjoy that fancy brain of another also counts as the 20 minutes of art.

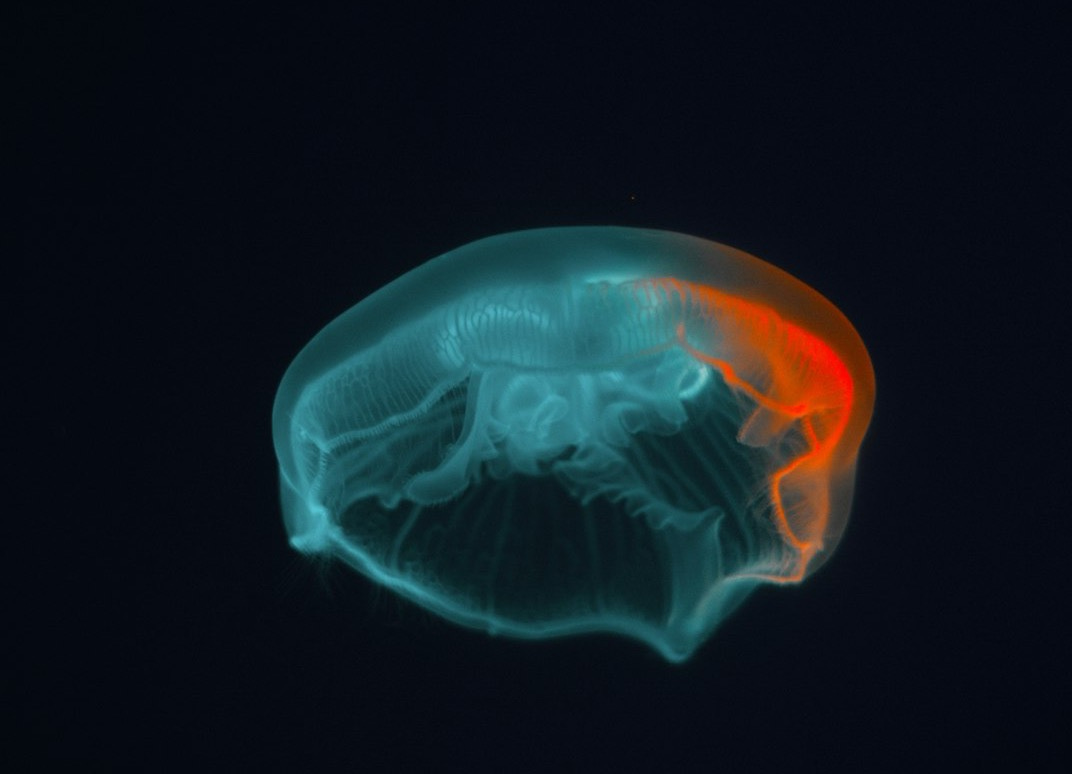

There is one thing I can’t do that I was reminded of the other day. I love the ocean. I love the waves, the smell, the salty water, and the temperamental nature of it. I grew up next to it. It compels me. My unrealistic desire is to be able to be underwater and just be, not with equipment. Just be. Alas, my lungs will not be very appreciative. I am not a great swimmer either. But my love for the ocean is never gone. Interestingly enough I can’t sail or be in a cruise. I can kayak, I can do white water rafting, and I can canoe. But being in a cruise or one of those large ferries like the one from Fajardo to Vieques in PR, is a recipe for a great disaster of the gooey kind. For me, as much as I fantasize about sailing, it is an invitation to enjoy it at a distance. And that is okay.

In the same way, when practicing art, we do not have to embrace it all or do all its variations to enjoy the benefits of it. We can do alternate things or enjoy others doing it. Have you ever been mesmerized by one of those reels where people are doing some artwork or craft methodically and repetitively? Like you can watch it all day? Exactly. it is calming.

The number of studies the Magsamen and Ross cited in the book is outstanding. Yet, the book is written for non scientists to appreciate and feel that time spent doing art is not and will never be wasted. While reading the book, I kept thinking that all our brains are fancy. We posses a unique capacity to create, to make, to develop, to tune in with music and memorable moments. Somehow specialization has created blinders. When I was doing research for my book, I remember reading somewhere that part of a wholesome education was to learn to draw. I don’t remember where I read it but I think it was in the book Learning to Draw by Ann Bermingham. It was not about mastery. It was about learning to observe and study the world. It was about being able to remember. Our keyboards can’t ever provide the salience that engaging in a drawing—to understand, retain, and remember—provides. It is not the same. Yes, we can type faster word by word almost. My mother was a secretary and her job was to take dictation and type what was dictated. And that is a great skill to have. But if our job is to understand, retain, and remember, we must engage our fingers, our bodies, and our mind. It is a simultaneous exercise in critical thinking, decision making, and mnemonics. It works and studies have proven it. In fact, back when drawing was it, there was little difference between the exercises to learn to draw and to learn to write cursive.

Technology is great until it isn’t. And if it robs me from developing and acquiring memorable knowledge, I will always prefer my fancy hands to feed my fancy brain. So, go and give your brain permission to be fancy, even if it is for 20 minutes.

Love,

Alma